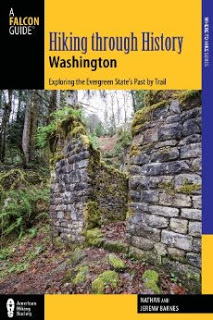

Fairfax Townsite

Explore what remains of Fairfax coal-boom ghost town along the Carbon River.

Total Distance: 2.0 miles

Total Ascent: 100ft

Highest Point: 1400ft

Total Ascent: 100ft

Highest Point: 1400ft

Difficulty: Moderate

Our Hiking Time: 2h 15m

Required Permit: None

Our Hiking Time: 2h 15m

Required Permit: None

To get there, take I-5 South to I-405. From I-405 take SR 167 south toward Auburn. In 20 miles take the SR 410 Exit toward Sumner/Yakima. Follow SR 410 for 12 miles to SR 165. Take a right and continue on SR 165 for about 10 miles through Carbonado to the Fairfax Bridge. Cross the bridge and continue on SR 165 for a half-mile. Veer left onto the Carbon River Road when the highway splits, and follow for just under two miles to a few large boulders on the left side of the road. There is a small pull out here. Park and follow the old roadbed down to the townsite. View Google Directions >>

The hike begins with a quick descent down toward the river, following the roadbed into town. Expect to navigate a little underbrush as you head down, as there is no formal trail maintenance happening in the area. Within a few minutes, you’ll be standing near the edge of the large meadow that was once Fairfax. From here, you can start exploring in any direction, or follow the loop we’ve put together. However, keep in mind that most of the structures are across the meadow to the north, including the swimming pool, the site of the old railroad bridge, and the coking ovens.

The easiest way to find most of these is to follow the faint impression of the main road through town, which cuts through the middle of the meadow. Keep an eye out for a large, artificial-looking hillock extending toward the river. A game trail here will lead you out to the river, and the cement foundation of the railroad bridge. Scramble up onto the embankment for a nice view of the Carbon River, as well as the rock jetty that was built to try and control flooding. Head back to the main road, and continue following it across the meadow and into the trees. The swimming pool foundation is just off to the right. From the foundation, head northwest toward a small stream. The coking ovens are tucked into the large mound on the other side of the water.

The most difficult part of this hike is finding it. There is almost nothing in the way of signage to indicate that you are in the right place. Eventually, after retracing our steps a few times, we found a small pullout that looked promising. Only then did we find the small laminated sign indicating that we were on the edge of Fairfax Forest. Beyond that, this is an easy walk through Washington’s mining history. However, while the hike is not strenuous, the area is undeveloped and some parts can be a little wet and muddy, so come prepared to get a little dirty. Fairfax is the largest ghost town we’ve visited, and there is much more to see than we’ve mentioned here. Consider exploring this section of the Carbon River Valley sometime soon.

However, over the next twenty years, the coal yields slowly dropped along with demand, as the country shifted toward oil and gasoline for its energy needs. By 1941 Fairfax was a ghost town, many inhabitants having hastily abandoned their homes and property. During this time Pierce County began to foreclose on properties in and around Fairfax for failure to pay property taxes. The lands remained as county “surplus” until 2002, when 640 acres were set aside as open space for public use, including the townsite and 80 acres of original old growth. Over the years, floods, fires, and salvaging destroyed most of the abandoned structures, and the forest continues to aggressively reclaim the townsite. Still, after seventy years you can find foundations, artifacts, and the long line of coking ovens.

The easiest way to find most of these is to follow the faint impression of the main road through town, which cuts through the middle of the meadow. Keep an eye out for a large, artificial-looking hillock extending toward the river. A game trail here will lead you out to the river, and the cement foundation of the railroad bridge. Scramble up onto the embankment for a nice view of the Carbon River, as well as the rock jetty that was built to try and control flooding. Head back to the main road, and continue following it across the meadow and into the trees. The swimming pool foundation is just off to the right. From the foundation, head northwest toward a small stream. The coking ovens are tucked into the large mound on the other side of the water.

The most difficult part of this hike is finding it. There is almost nothing in the way of signage to indicate that you are in the right place. Eventually, after retracing our steps a few times, we found a small pullout that looked promising. Only then did we find the small laminated sign indicating that we were on the edge of Fairfax Forest. Beyond that, this is an easy walk through Washington’s mining history. However, while the hike is not strenuous, the area is undeveloped and some parts can be a little wet and muddy, so come prepared to get a little dirty. Fairfax is the largest ghost town we’ve visited, and there is much more to see than we’ve mentioned here. Consider exploring this section of the Carbon River Valley sometime soon.

History

Like Franklin and nearby Melmont, Fairfax sprang up around rich coal deposits. Founded in 1892, it was named for Fairfax County, Virginia by W.E. Williams and platted in 1897 when the Northern Pacific Railway was extended from Carbonado out to Fairfax. The town quickly expanded, and by 1901, 60 coking ovens were producing 252,000 tons of furnace grade coal a month. The population of Fairfax grew with the rising demand for coal during World War I, reaching 500 people by 1915. Access to the town was limited exclusively to railroad car until December 17, 1921, when the county extended the road over the Carbon River and into Fairfax.However, over the next twenty years, the coal yields slowly dropped along with demand, as the country shifted toward oil and gasoline for its energy needs. By 1941 Fairfax was a ghost town, many inhabitants having hastily abandoned their homes and property. During this time Pierce County began to foreclose on properties in and around Fairfax for failure to pay property taxes. The lands remained as county “surplus” until 2002, when 640 acres were set aside as open space for public use, including the townsite and 80 acres of original old growth. Over the years, floods, fires, and salvaging destroyed most of the abandoned structures, and the forest continues to aggressively reclaim the townsite. Still, after seventy years you can find foundations, artifacts, and the long line of coking ovens.

Nearby hikes

Similar Difficulty

Similar Features